When coins were withdrawn from circulation in the northern states during the Civil War, opportunists began minting private pennies that became de facto legal tender throughout the Union. The coinage of a few cents may seem like small change, but in 1863 alone, almost 9,000 different token designs, depicting everything from patriotic flags to beer barrels, were struck. Some so closely resembled real cents that the government banned private mints in 1864.

Coin collector Ken Bauer, who is a member of the Civil War Token Society, spoke to us about his almost lifelong interest in Civil War tokens, as well as the website he recently built to help new enthusiasts amass their own collections.

Collectors Weekly: How’d you get into Civil War tokens?

Ken Bauer: I started collecting Civil War tokens in 1973. It was a lower-cost alternative to coins, which I’d been collecting since I was six years old. Coin collecting was a pretty common hobby for kids in the 1960s. You’d go through the change in your pockets and fill up the holes in your blue Whitman coin folders. Quarters were kind of out of my league—today I’m sorry I didn’t collect standing liberty quarters back then—so I pretty much confined myself to pennies, nickels, and dimes.

After I was married, after college, I discovered some Civil War tokens in a coin shop. I thought they were really cool, and unlike coins, you could get rare ones in good condition fairly inexpensively. Plus, each one had a story to tell.

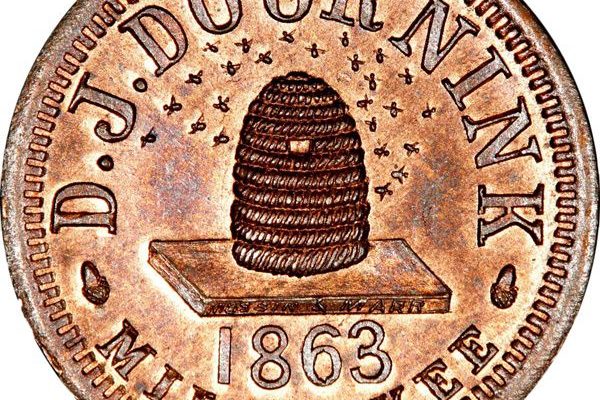

Die sinkers such as H.D. Higgins made tokens for themselves and other merchants. A beehive, such as the one at top, was meant to signify stores that were literally hives of activity.

Over the years, I photographed the Civil War tokens I collected and inventoried them in a spreadsheet. I only have 700 or so out of 10,000 different varieties, so when I started my Civil War tokens website in June of 2011, I knew I had to come up with something other than a comprehensive catalog of storecards and patriotic tokens as George and Melvin Fuld had done. I wasn’t expecting to supersede the Fulds; their work, especially the rarity estimates, is a huge gift to collectors.

My idea was to create a website that would make it easy for non-coin people to decide to collect tokens with, say, beer glasses or beehives or boots on them, so they could fill in a new kind of virtual Whitman blue book to complete small sets. I also list the Fuld index numbers for each coin.

Collectors Weekly: How does your system differ from Fuld’s?

Bauer: The Fuld storecard book, which is a catalog of all Civil War tokens with a merchant’s name or initials on them, is organized by state, city, and then alphabetically by merchant within that city. It kind of encourages people to pick a place like Milwaukee and then try to get one token from every merchant in town. That’s how storecard tokens tend to be collected.

Die sinker John Stanton of Cincinnati, who struck this storecard, is considered one of the finest craftsmen of the era.

Patriotic tokens, which have patriotic slogans and images on them, are in a separate catalog. In that book, there are photographs of each of the 537 dies that were used to strike the tokens. The Fulds listed all the obverse-reverse die combinations, and whether the metal struck was copper, brass, or what have you. People tend to collect patriotics by trying to get them all, but since there are thousands of patriotic tokens, that’s not really very obtainable.

So that’s why I added ID information, so a new collector could collect by what I call “type sets.” For example, if someone really likes the look of the flying eagles, they can click on the flying eagle description and see that there are six flying eagle tokens and try to get one of each. All of the description pages and individual photos include the Fuld die numbers for cross referencing, but type sets like flying eagles are my invention.

Collectors Weekly: So who decided that GWe, for example, should designate George Washington equestrian tokens?

Bauer: I did. I made all that stuff up.

Collectors Weekly: Not the term storecards, though, right?

Bauer: No, that’s been used for a long time, going back to the 19th century. It refers to tokens that have merchant names and advertising on them. I don’t know its origins, but I do know there are more storecard varieties than patriotics, roughly 8,000 versus 2,000, although those numbers have nothing to do with rarity. Relatively common Civil War tokens are designated R1, which just means that more than 5,000 are thought to have survived. If a token is an R10, then there’s only one example known to exist.

Some clever die sinkers got around potential charges of counterfeiting by positioning their coins as IOUs.

Collectors Weekly: What about the C designations?

Bauer: I made those up, too. For the Fulds, all common token were R1s, but when you look at tokens aggregated in terms of type, they can be more common than that. For instance, there’s an Indian head made by an engraver named John Stanton of Cincinnati. It’s a very distinctive kind of Indian head and it shows very fine craftsmanship.

Stanton made up to 30 different dies with the same Indian head on it. The only differences are how the feathers point to the stars. It’s just how the elements were laid out on the token. Any one of those individual coins may be an R3 (which means fewer than 3,000 survive), but if you take the literally thousands of examples of the 30 Stanton Indian head dies from 1863 as a group, the type is more common than that. Stanton’s 1863 Indian head type is really a C4, meaning more than 200,000 token examples of that type are believed to exist.

The flying eagle token on the left bears a striking resemblance to the real coin on the right (photo courtesy indiancent.com).

Collectors Weekly: You’ve also got a section on cent facsimiles.

Bauer: That’s another invention of mine. The storecards are easy to classify because they have a merchant name on them, but there are an awful lot of tokens in the patriotic book that aren’t really patriotic at all. The intent of the tokens in the cent facsimiles grouping appears primarily to cause a person receiving a token in change to mistake it for a real cent. Many of these tokens have an Indian head on the front or a flying eagle, because the flying-eagle cents from 1857 and 1858 were still in circulation. I posted a real flying eagle in the flying eagle section of the site so people could compare the tokens to the real thing. You can see how similar they were.

“During the Civil War, northern die sinkers were literally minting money.”

The reason why we’re talking about these tokens at all is because the counterfeiting laws at the time were pretty vague about copper coinage. They were very clear about gold and silver coinage—you couldn’t make copies of those—but they were really not clear about copper and, hence, copper cents. So the die sinkers were willing to give it a try, but at the same time they were being cautious.

That’s how you end up with tokens in the Nc or the No groups. In general, the reverses of these tokens look fairly similar to the Indian head cents that were minted at the time. At first glance these might seem like they were the same thing, except for that disclaimer: “Not One Cent.” Again, that’s not especially patriotic.

As the front and back of this token shows, the complaint that there’s plenty of money to make war but little to pay for its impact on the families of soldiers is not new.

Collectors Weekly: What did the words “Not One Cent For The Widows” refer to?

Bauer: Most of these dies were mixed and matched pretty freely. That particular one got matched up with an obverse die that shows an Indian head with the words “Millions For Contractors.” Turn it over and on the back it says “Not One Cent For The Widows,” which is what I mean when I say each one of these tokens has a story to tell. I don’t know all the details, but obviously the war department was spending lots of money on cannons, mortars, and materials for the war machine. Apparently something about the pensions for widows or soldiers killed in action was not to the liking of the person making this token.

Collectors Weekly: Did the tokens vary in their quality?

Bauer: Yes, in fact that’s one of the things I find most interesting about the Civil War tokens, the range of quality. I mentioned John Stanton of Cincinnati. There was also Scovill Manufacturing Company in Connecticut, which produced tokens nearly equal in quality to what was being produced by the U.S. Mint. At the other end of the scale were some of the Midwest die sinkers who were literally doing this in their basement or out in a woodshop, hand-cutting their dies, spelling blunders and all, and striking their tokens on hand-turned screw presses.

In the section of my site on grading, you’ll see references to the kinds of issues that collectors wrestle with in terms of the quality of the strike and the quality of the planchet, or blank. There are tremendous variations in the quality of these things. A lot of the Civil War token collectors really like the stuff that shows evidence of cracked dies and errors.

Coins and tokens are referred to as being “struck” even though they are made on a coining press, which was the subject of this token.

Collectors Weekly: You said some of the die sinkers had screw-down machines. In that case, is the coin, strictly speaking, being struck?

Bauer: Yes, although it’s not struck with a hammer. I think all of these coins were either struck with a screw press like the one shown in the Mf group within scorecards or in a steam-operated press. A number of die sinkers and companies were mechanized to that extent during the Civil War. You could achieve a much more consistent evenness of strike with a steam press.

Collectors Weekly: What was in it for the die sinkers?

Bauer: There had always been advertising tokens produced many years before the Civil War in lots of sizes. There were also political medals, which were the forerunners of the celluloid political button that people wear. So there were already engravers and die sinkers out there making this sort of stuff.

Here’s where it got interesting for the die sinkers. Up until 1857, the U.S. government minted large cents. They were big, clunky, and pretty unpopular, but each one had one cent’s worth of copper in it. That was true for all the coins of that era—their bullion value nearly equaled their face value. That’s what people wanted.

The flying eagle cents dated 1856 were about the thickness of a nickel and the diameter of the current cent. So they were much thicker and had a mixture of copper and nickel in them. Still, the bullion value of the flying-eagle cent, these copper-nickel cents, was about one cent, nearly if not exactly.

The Civil War tokens, on the other hand, were really the forerunners of the current Lincoln cent because they’re the same diameter and thickness as a Lincoln cent but they were made, for the most part, of pure copper, which meant their intrinsic value was only about two-tenths of a cent at that time. It was quite a racket. Die sinkers would make tokens that cost them two-tenths of a cent and sell them to merchants for nine-tenths of a cent. The merchants would make a tenth of a cent for their trouble. The die sinkers were literally minting money.